Imagine the old man’s eye staring back at you, a pale blue film that drives a man mad. In Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart,” the unnamed narrator’s obsession pulls you into his twisted mind. You feel his racing pulse, hear the imagined heartbeat thumping under the floorboards. That character sticks with you because he’s real in his flaws and fears. He isn’t just a killer; he’s a bundle of nerves and excuses.

Short stories thrive on strong characters. They carry the whole tale on their shoulders. Without depth, your story falls flat. Readers want folks they can root for or fear, not cardboard cutouts. Interesting characters spark emotions and make plots hum. They face choices that mirror our own struggles.

But how do you build them right? What if your hero feels too perfect or your villain too simple? Common slips, like skipping real motives or dumping info, eliminate the effect. This article dives into creating real-like characters for short stories. We’ll explore character motivations and their impact on the overall story. Plus, we’ll master “show, don’t tell” to let actions speak loud. You’ll get tips to avoid pitfalls and make your writing pop. Get ready for steps that will turn your characters from flat sketches to realistic poeple

Understanding Authentic Character Creation

Real characters pull readers in like old friends at a campfire. They make short stories breathe.

Defining Character Authenticity in Short Stories

Authentic characters feel like people you know. They have layers: strengths mixed with weaknesses, dreams tangled with regrets. Think of Alice Munro’s folks in her collections. Her women wrestle quiet pains that hit home. Psychological truth matters here. It keeps characters from seeming fake or boring.

Flat characters bore us fast. They lack the flaws of the real life. To build depth, try a character questionnaire. Ask: What’s their biggest fear? What habit annoys them? This uncovers hidden bits. Authentic character development starts with truth. It fits the tight space of short stories, where every word counts.

Avoiding Common Stereotypes

Stereotypes sneak in easy for new writers. The tough cop or shy librarian? They feel lazy. Subvert them. Give the cop a soft spot for stray dogs. Make the librarian bold in secret. This adds surprise and life.

Research helps. Dive into real lives from different places. Read “The Elements of Style” by Strunk and White for tips on clear, honest portraits. Keep it short and true. Compelling characters in short stories shine when they break molds. They draw us closer, not push us away.

Building Backstories That Matter

Backstories shape who your character is now. But in short stories, don’t overload. Pick key events that echo in the present. Reveal them bit by bit through actions or hints.

Raymond Carver nails this in “Cathedral.” The blind man’s past colors his chat with the narrator. It builds without bogging down. Tip: List three big moments. Weave them in as needed. This keeps your tale moving while grounding the person.

Exploring Character Motivation: The Driving Force

Motives push characters forward. They create sparks that light up your short story.

Types of Motivation in Fiction

Motivations split into two camps: inside ones and outside pulls. Intrinsic drives come from the heart, like a quest for love. Extrinsic ones hit from the world, such as dodging a boss’s wrath.

Anton Chekhov’s tales show this clash. In “The Lady with the Dog,” a man’s inner longing battles social rules. It stirs real tension. Map these early when you outline. Check for steady flow. E.M. Forster in “Aspects of the Novel” talks round characters fueled by such wants. They feel alive. Character motivation techniques like this make your story pulse with purpose.

Linking Motivation to Plot and Conflict

Motives breed fights that drive the plot. A character’s want rubs against roadblocks, and boom—tension rises.

Take Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” The grandma’s selfish urges lead straight to doom. Her self-preservation twists the road trip into horror. Use a chart: Link wants to turning points. In short stories, this punch hits hard due to the quick pace. It keeps pages flipping.

Revealing Motivation Through Internal Monologue

Peek inside a character’s head to show their drives. But keep it light—no long rants.

Stream-of-consciousness works in bits. It lets thoughts flicker like real worries. James Joyce shaped this for modern shorts. Use it to hint at hidden urges. Readers catch the why without you spelling it out.

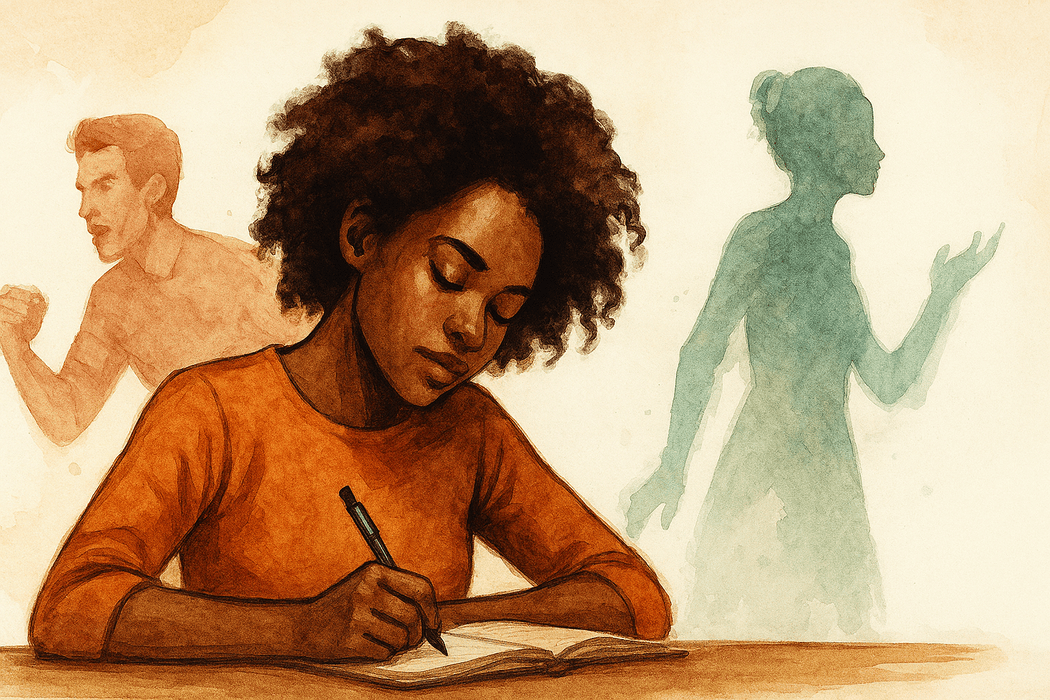

Mastering “Show, Don’t Tell” for Compelling Characters

“Show, don’t tell” brings characters to life. It paints pictures instead of listing facts.

The Basics of Show, Don’t Tell

This trick means you let readers see and feel, not just hear summaries. In short stories, space is gold, so actions beat blunt words.

It hooks folks deeper. Swap “She felt sad” for tears on her cheek or a sigh in the rain. Chekhov said it best: Don’t say the moon shines; show its gleam on shattered glass. Show don’t tell in writing builds trust. Readers fill in the rest.

Applying It to Character Emotions and Traits

Reveal feelings through what they do, say, or touch. A clenched jaw shows rage better than “He was mad.”

In Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” talks hide hurts. The couple’s pauses scream trouble. Tip: Scan your draft. Spot telling lines. Rewrite with sights, sounds, smells. This makes traits stick. It turns quiet moments into mirrors of the soul.

Integrating Show with Motivation Revelation

Blend showing with motive hints for smooth flow. Let deeds uncover wants, no big reveals needed.

A hand shaking on a door handle might betray fear of change. Practice prompts: Have a character chase a secret goal through acts. Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Steering the Craft” pushes for sharp details. It makes drives feel earned.

Techniques for Depth and Engagement

These tools layer on more punch. They tie everything together for short story magic.

Using Dialogue to Reveal Character and Motivation

Talks show who people are and what they crave. Words slip out hints of deeper stuff.

In Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” chit-chat hides dark plans. It builds chills. Tip: Let lines suggest, not spell out. Cut fluff. Make voices unique—short barks or drawn sighs. Dialogue in short story writing uncovers layers fast.

Sensory Details and Setting to Show Inner Worlds

Places and senses echo a character’s mind. A stormy sky matches inner turmoil.

Poe used this in his moody rooms to amp fears. Add smells of rain or rough wood under fingers. It mirrors wants without words. Tip: Pick details that fit the drive. This amps the “show” effect.

Balancing Show and Tell in Limited Word Counts

Short stories need pace, so mix both. Show big scenes; tell quick bridges.

O. Henry’s twists rely on this. A line of tell sets up the surprise show. Tip: Save telling for moves between beats. Focus show on heart moments. It keeps things tight and taut.

Conclusion

Authentic characters, fueled by strong motivations and shown through vivid acts, transform short stories. We’ve covered building real backstories that shape now, mapping drives to spark conflicts, and using “show, don’t tell” to let readers feel the pulse. Layered personalities avoid stereotypes. Sensory hints and smart talk reveal depths without waste.

Key steps: Grab a questionnaire for hidden traits. Chart wants against plot turns. Rewrite tells into actions—clenched fists over flat says. In your next draft, pick one tip. Show a motive through a glance or word. Experiment now. Craft folks that linger like Poe’s haunted heart. Your readers will thank you with nods and chills.

Practise: The “Show, Don’t Tell” Character Interview

Instead of writing a backstory, you will reveal your character’s personality and motivations through a scene. Your character is being interviewed by an unseen person about a past event. Your job is to make your readers understand the character’s personality, mood, and deeper truth by describing only their actions, physical reactions, and dialogue—not by stating how they feel.

Instructions:

- Select a Character Type: To start, choose a simple, classic character.

- Iteration 1 (Recommened, This Is The Easiest): A hero who is actually a coward.

- Iteration 2: A villain who believes they are doing the right thing.

- Iteration 3: A wise old mentor who is hiding a foolish mistake.

- Iteration 4: A loyal sidekick who is secretly resentful.

- Choose a “Trigger” Event: This is the incident the interviewer is asking about.

- For the coward-hero: A moment where your character was publicly praised for a “brave” act that was actually a clumsy accident.

- For the other archetypes: Select an event that reveals the hidden contradiction you chose in step one.

- Write the Scene: Your interview scene must include the following:

- Use an interview format. The interviewer’s questions are never explicitly written, but your character’s responses should make the questions clear to the reader.

- Focus on physical actions. Show, don’t tell. Instead of writing “He was nervous,” write what his nervousness looks like. Does he tap his foot, straighten his tie repeatedly, or refuse to make eye contact?

- Use sensory details. Include what the character sees, hears, and touches. Perhaps they focus on a small, insignificant object in the room to avoid facing their own lies.

- Incorporate a “tell” and a “show.” You may, in one place, include a classic “telling” phrase. Immediately after, write a much more descriptive version that “shows” the same emotion. Your character’s struggle to find the right words will reveal their inner conflict.

Example of showing and not telling for the Coward-Hero:

Instead of: “He was nervous, but he wanted to appear brave.”

Show it like this:

He cleared his throat, adjusting the collar of his stiff shirt. His eyes, fixed on the scuff mark on his worn shoe, refused to meet the reporter’s. “I—I just did what anyone would do.” He shrugged one shoulder, a motion that seemed more like a twitch.

(After the interviewer’s implied question about the chaos.)

“It was chaos.” His lips were a thin, dry line. A show of bravado: he puffed out his chest, but a quick twitch in his left eye gave away the lie. “Just… a lot of smoke.” He picked at a stray thread on his sleeve, his gaze darting around the room, settling anywhere but on the person asking the questions.